Download the Transfer Playbook

The Transfer Playbook

SECOND EDITION

A Practical Guide for Achieving Excellence in Transfer and Bachelor’s Attainment for Community College Students

Authors

Tania LaViolet, Kathryn Masterson, Alex Anacki, Josh Wyner

(The Aspen Institute)

John Fink, Aurely Garcia Tulloch, Jessica Steiger, Davis Jenkins

(CCRC)

Acknowledgments

This research was conducted through a partnership between the Aspen Institute College Excellence Program and the Community College Research Center (CCRC) at Teachers College, Columbia University, with funding from the Belk Center for Community College Leadership and Research, College Futures Foundation, ECMC Foundation, and Kresge Foundation. The research reported here was also supported by the Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education, through Grant R305B200017 to Teachers College, Columbia University. The opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not represent views of the Institute or the U.S. Department of Education. The authors gratefully recognize the contributions of Tatiana Velasco and Mariel Bedoya-Guevara, who supported the quantitative analysis for this research; our data providers and collaborators at the National Student Clearinghouse Research Center; Nicole Zefran and Nora Ngo for their project management and administrative support; Heather Adams for her early contributions to the research and management of the project; the members of the Tracking Transfer and Transfer Playbook Advisory Boards (Charles Ansell, Pamela Burdman, Terry Brown, Bridget Burns, Bettina Celis, Monica Clark, Darla Cooper, Marielena DeSanctis, Wil Del Pilar, Nathan Evans, Yvette Gullatt, Audrey Jaeger, Andrew “Drew” K. Koch, Michal Kurlaender, John Lane, Donna Linderman, Alexandra “Lexa” Logue, Aisha N. Lowe, Janet Marling, Michelle Marks, Jason Rivera, Olga Rodriguez, Angel M. Royal, Edward Smith-Lewis, Lisa Stich, David Troutman, Janie Valdes, Lia Wetzstein) for their strategic guidance; Voice Design Collective for their design services; Liane Guenther for her editorial support; and Kristin Terchek O’Keefe and Burness Communications for their support in disseminating the report. Last but not least, the authors would like to express our deep gratitude for the hundreds of senior leaders, practitioners, faculty members, and transfer students who took the time to share their insights with us.

The Aspen Institute College Excellence Program

The Aspen Institute is a global nonprofit organization whose purpose is to ignite human potential to build understanding and create new possibilities for a better world. Founded in 1949, the Institute drives change through dialogue, leadership, and action to help solve society’s greatest challenges. The Aspen Institute College Excellence Program supports colleges and universities in their quest to achieve a higher standard of excellence, delivering credentials that unlock life-changing careers and strengthen our economy, society, and democracy.

Community College Research Center

The Community College Research Center (CCRC), Teachers College, Columbia University, has been a leader in the field of community college research and reform for more than 25 years. Our work provides a foundation for innovations in policy and practice that help give every community college student the best chance of success.

Many community college entrants aspire to earn a bachelor’s, and yet, for the past decade, fewer than one in five were successful. What would it take to double or triple our current transfer outcomes?

Table of Contents

-

Strategy 1: Prioritize Transfer at the Executive Level to Achieve Sustainable Success at Scale

-

Essential Practice 1: President-led, team-based, well-resourced partnerships

-

Essential Practice 2: End-to-end redesign of the transfer student experience

-

Essential Practice 3: Routinized, transfer student-centered systems and processes

-

Strategy 2: Align Program Pathways and High-Quality Instruction to Promote Timely Bachelor’s Completion within a Major

-

Essential Practice 1: Four-year sequences that promote learning and major progression

-

Essential Practice 2: Systematized translation of maps into tailored education plans

-

Essential Practice 3: Strengthened instruction, academic support, and curricular alignment

-

Strategy 3: Tailor Transfer Advising and Nonacademic Supports to Foster Trust and Engagement

-

Essential Practice 1: Early, sustained, and inevitable advising systems

-

Essential Practice 2: A trained, knowledgeable, and caring advising corps

-

Essential Practice 3: A transfer-specific approach to holistic success

Publication Guide

Institutions Studied

2-Year Institutions:

Arizona Western College, Yuma, AZ

College of Southern Maryland, La Plata, MD

Durham Tech Community College, Durham, NC

Imperial Valley College, Imperial, CA

Northern Virginia Community College, Annandale, VA

Northwest Vista College, San Antonio, TX

Prince George’s Community College, Largo, MD

Tallahassee State College, Tallahassee, FL

4-Year Institutions:

CUNY John Jay College of Criminal Justice, New York, NY

East Carolina University, Greenville, NC

George Mason University, Fairfax, VA

Northern Arizona University-Yuma, Yuma, AZ

San Diego State University, San Diego, CA

San Diego State University-Imperial Valley, Calexico, CA

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, AR

University of North Texas, Denton, TX

Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, VA

KEY IDEA

This icon indicates the key ideas of an essential practice

FIELD EXAMPLE

This icon indicates a field example of key ideas associated with an essential practice

QUICK LINK

This icon indicates an opportunity to quickly jump to that content in the report.

Foreword

Dear Readers,

Increasing the number of community college students who transfer and earn bachelor’s degrees should be a national priority. Each year, hundreds of thousands of new community college students aim to earn a bachelor’s, but only a small percentage eventually achieve that goal1. Meanwhile, improving bachelor’s attainment rates could strengthen our country in many ways: helping fill persistent shortages of teachers, engineers, nurses, and other professionals; developing the talent that could lead to the next major advancements in public health, international peace, and the arts; and fostering a more engaged citizenry. More bachelor’s degrees would also increase economic mobility and opportunity for more Americans by opening doors to the majority (and growing number) of high-paying, family-sustaining jobs, including careers in research, management, business ownership, and leadership in every sector.

There is immense potential in the dreams and ambitions of bachelor’s-intending community college students—and the many who may have counted themselves out but have the ability to complete a bachelor’s and expand their career horizons. This Playbook outlines how colleges can help foster and actualize those dreams and ambitions by engaging in practices that dramatically increase the number of students who transfer and complete bachelor’s degrees.

The second edition of the Transfer Playbook is the culmination of two years of quantitative analysis and qualitative fieldwork that builds on the Aspen Institute College Excellence Program and the Community College Research Center’s 2016 Playbook and subsequent work with thousands of higher education leaders and practitioners nationwide. It aims to empower change agents to more fully develop the many talented students at our nation’s community colleges.

The examples featured in this Playbook come from colleges in cities, suburbs, and rural America. Our conclusion: Transfer excellence is within reach of every school; no institutional characteristic prevents leaders, staff, and faculty from achieving it.

This work could not have been done without the hundreds of educators and students who shared their time, insights, and expertise with us over the last two years. We’ve witnessed the power of practitioners and advisors who transformed student experiences, faculty members coming together to align expectations and deliver excellent teaching, and presidents and senior administrators making transfer student success a top priority so their institutions could create lasting, systemic change.

We hope you, too, find inspiration in their work

With optimism and hope for the future,

Tania LaViolet (The Aspen Institute) and John Fink and Davis Jenkins (CCRC)

Introduction

Every year, millions of students enroll in community colleges, and many of them strive to transfer to a university and earn a bachelor’s degree. Their motivation: the life-changing economic opportunity that degree confers.

Their aspirations are rooted in evidence. According to the Georgetown Center for Education and the Workforce, a growing proportion of jobs in the future will require at least a bachelor’s degree.2 In 2031, among “good jobs” that will pay family-sustaining wages, the center projects 66 percent will be held by workers with a bachelor’s degree or higher, up from 59 percent in 2021.

Students who attend community college have a lot to gain from attaining a bachelor’s degree—and so does our country. A national strategy to improve transfer outcomes could create great societal benefits, while also uplifting those historically farthest from educational and economic opportunity and mobility.

Nearly three-quarters of community college students come from families in the lower half of income distribution.3 And nearly 50 percent of all Hispanic undergraduates, 43 percent of Black undergraduates, 49 percent of first-generation students, 42 percent of military-affiliated undergraduates, and 40 percent of students from rural areas are enrolled in community colleges.4,5 These students are more likely than four-year college students to be parents, come from foster care, and represent a diversity of ages and life experiences.6,7

Behind these statistics are compelling life stories, and we learned many of them during our research: students who overcame homelessness, drove for hours to get to class, and worked several jobs to make ends meet. We heard stories of grit and persistence and of trusted advisors and faculty members working with students to help them attain bachelor’s degrees when others might not have believed it possible. We met students with talents that could take them anywhere, but they chose to stay close to home and their support networks and, after graduating, to give back to their families and communities.

Unfortunately, many community colleges and universities have not adequately addressed the myriad obstacles—many created by the institutions—that stand in the way of transfer students’ success. Navigating current transfer pathways relies too heavily on the determination of individual students and their supporters.8 The result: The national bachelor’s attainment rate among students who start college at a community college remains below 20 percent.9 Bachelor’s completion rates are even lower for low-income, Black, Hispanic, and adult community college starters, which range from 6 percent to 11 percent. Efforts to improve outcomes overall will be difficult, if not impossible, without a strong focus on ensuring every student—regardless of their background—has the opportunity to achieve success unencumbered by undue institutional burdens.

The field should strive not only to make improvements but to achieve excellence in transfer and bachelor’s attainment rates.

Even students who transfer and earn a bachelor’s can face barriers that delay progress toward their degrees and increase costs. Indeed, while colleges often tout the savings that can result from “2+2” pathways (i.e., two years at a community college’s tuition rate and two years at a university’s), only 18 percent of transfer students complete their degrees within two years of transferring and realize those savings. The good news: Better outcomes are within reach.

In our research for this Playbook, we found exceptional institutions by looking at data and interviewing college leaders, administrators, practitioners, and students. We synthesized our findings into a practical, three-part framework that can be adapted by leaders, practitioners, and faculty members on community college and university campuses. In the coming years, we hope this Transfer Playbook will help colleges strengthen transfer pathways and, in turn, transform millions of lives.

Raising the Bar for Transfer

Transfer and bachelor’s attainment rates for students who start in community colleges have remained virtually unchanged since we started tracking transfer in 2015.10 The field should strive not only to make improvements but to achieve excellence in transfer and bachelor’s attainment rates.

At the time of this research, colleges with the strongest overall transfer outcomes—those in the top 10 percent—exceeded transfer rates of 52 percent, while colleges with the strongest bachelor’s completion outcomes for transfer students exceeded rates of 61 percent.11 These outcomes show it is possible for community colleges to successfully transfer the majority of their students, who then earn bachelor’s degrees at rates comparable to those who start directly at four-year institutions.12 If community colleges and universities across the nation achieved this level of excellence in transfer, they could double the bachelor’s attainment rate of community college students from 16 percent to 32 percent (Figure 1).

What would it take to get there? The second edition of the Transfer Playbook provides practical guidance rooted in a data-driven study (Appendix 1) of the practices community colleges, universities, and transfer partnerships used to achieve relatively strong outcomes overall, and specifically for low-income, Black, and Hispanic students (Figure 1). These schools’ successes demonstrate that doubling the bachelor’s attainment rate for community college students is within reach.

It is important to note that none of the institutions or partnerships we researched exhibited the full suite of practices outlined in this Playbook. However, we hypothesize that by combining the exemplars’ efforts into a comprehensive, idealized framework, higher education leaders and practitioners can adapt it to meet their students’ needs and achieve strong outcomes for all—and at scale.

Three Strategies for Achieving Excellence in Transfer and Bachelor’s Attainment

This Playbook is organized around three broad strategies we observed in exemplary community college and university partnerships.

Consistent Themes Across the Framework

Our research gave us a clear understanding of what set exemplary colleges apart and why their practices were so powerful. Some consistent, underlying themes included:

Institutional proximity can be leveraged.

Many students want—or need—to stay close to home, highlighting the importance of local pathways between community colleges and four-year universities that serve students at scale. Unfortunately, too many neighboring community colleges and universities leave barriers to transfer success unaddressed, passively enrolling students who rely on the proximity of their institutions. Exemplary partnerships in our research took advantage of their institutions’ physical proximity and created regionally relevant pathways and supports that could grow the number of students they enroll and graduate, especially among populations least likely to pursue any college credential.

All students need ready access to systems that help them navigate high-stakes choices, delivered by people who care.

For many community college students, missteps in course, major, or transfer destination selection can have financial and opportunity costs that determine whether they complete their degrees or stop out indefinitely. These high-stakes choices are best made by students with the support of advisors and other staff who can empathize with students’ unique and often challenging circumstances to personalize guidance. At most institutions, many staff members do this exceptionally well. However, an approach that relies on their individual initiative and understanding instead of a universal, coordinated system will inevitably result in some students getting left behind, often those who need support the most. The exemplars in our research built systems and tools that ensure most students—not just those who seek help—receive timely, accurate guidance by staff trained to be welcoming, encouraging, and empathetic.

The strongest partnerships include universal systems and initiatives, often informed by what works for historically underserved student groups.

Our research and fieldwork found that many programs that aim to help specific populations achieve strong outcomes and minimize, if not eliminate, disparities for low-income, Black, and Hispanic students. However, too few of these programs reach students at scale. The exemplars in our research use these programs to test and prove what is effective for supporting students who face considerable challenges, and they incorporate key programmatic elements into their universal systems, such as technology, advising, and academic and nonacademic support offices.

Leadership is needed at both the mid and senior levels.

Our interviews revealed that strong outcomes for some students could be achieved through the efforts of one or a handful of transfer champions, often student-facing staff or faculty members. When their grassroots movements were recognized, elevated, and invested in by presidents and senior leaders, they could be brought to scale and institutionalized in such a way that transfer efforts were resistant to the disruptive effects of turnover. Unfortunately, our research also revealed the opposite can happen: When scaled transfer models have not been built and institutionalized before key transfer champions left, their work—and impact—did not continue.

Strategy 1: Prioritize Transfer at the Executive Level to Achieve Sustainable Success at Scale

Summary: This strategy comprises three essential practices, each featuring several key ideas:

Achieving much stronger transfer outcomes overall as well as for those least likely to attain a bachelor’s degree often requires major institutional and partnership reforms. That explains why we found prioritizing transfer at the executive leadership level—especially the presidency—was common among the colleges featured in this research. The following section explains what this looks like in practice.

Essential Practice 1

President-led, team-based, well-resourced partnerships

Presidents who lead effective transfer partnerships prioritize transfer student outcomes, charge senior-level staff to mobilize teams that collaborate and implement major transfer reforms, and allocate personnel, financial investments, and their own time to advance those reforms.

At the institutions we researched, both community college and four-year presidents understood the central role transfer student success played in both accomplishing their educational mission and achieving their business and enrollment objectives. They routinely called attention to transfer reform initiatives and emphasized the importance of transfer partnerships to their institutions and regions. They collaborated with presidents at their partner institutions to develop a shared vision for what they wanted to accomplish together, fostering a sense of common purpose and laying a solid foundation for successful transfer reform.

KEY IDEA

Shared, president-led vision for the partnership’s impact, clearly communicated with key stakeholders

FIELD EXAMPLES:

The presidents of Arizona Western College (AWC) and Northern Arizona University (NAU) share a priority: More local students must attain a bachelor’s degree if the economies of their regions and their state are to thrive. The two institutions, which have shared space on AWC’s Yuma campus since 1988, paired up to pursue AWC’s “Big Hairy Audacious Goal” of doubling the rate of baccalaureate attainment in Yuma and La Paz counties by 2035.13

Undergirding the goal is a growing need among employers and workforce development partners in the two rural counties for workers with bachelor’s degrees. For example, the Yuma Proving Grounds, a military operation near AWC/NAU-Yuma, needs mechanical engineers to work at its military facilities. And Yuma’s agricultural industry needs civil engineers for the region’s growing transportation infrastructure. The college presidents also know that too many people in the region live in poverty and too few have bachelor’s degrees. By working together to increase bachelor’s attainment, the colleges can connect more residents to those good-paying jobs.

Achieving this “Big Hairy Audacious Goal” is a centerpiece of AWC’s strategic plan. And because AWC’s leaders decided achieving it would require strong university partnerships, they chose not to offer bachelor’s degrees (in contrast to other Arizona community colleges). The goal is core to NAU’s strategic agenda, too. One of its priorities is to “set NAU on a path to awarding high-value credentials to over 100,000 people by 2035 and ensure that at least two out of three NAU graduates work and live in Arizona.” To do that, NAU needs more community college transfer students to enroll and graduate.

These shared goals have translated into substantial opportunities for students and the region. One example: NAU-Yuma now offers mechanical engineering because the presidents of AWC and NAU jointly lobbied the Arizona legislature for $5 million to start the program.14 And while all the funds went to NAU, the AWC president saw it as a victory for all. “If you are keeping score by who got the money, that was wasted time,” he said. “If you’re keeping score by [if] we have a mechanical engineering program here on campus, then…we won.”

Northern Virginia Community College (NOVA) and George Mason University have a long history of transferring thousands of students between them each year. Yet, for years, too many students encountered unnecessary barriers to transferring their credits and finding the right support services to help them reach their goals. As a result, too many students who could have transferred didn’t. Beginning in the early 2000s, presidents at both institutions began to recognize the pipeline had untapped potential that could be unlocked with the right investments and improvements. The NOVA and George Mason presidents began to meet more regularly to understand each other’s priorities and challenges. Over multiple presidencies, the two institutions prioritized working together on transfer, leading ultimately to the creation of a program that has become a national model and is profiled throughout this Playbook.

The institutions’ regional context gives a clear sense of why transfer rose to be among the top of their presidents’ priorities. At both NOVA and George Mason, transfer students’ success is closely tied to the institutions’ and partnerships’ pivotal roles in meeting regional workforce and talent demands. The two schools have large campuses in Fairfax County, Virginia—a densely populated, diverse community just outside Washington, DC. The region is home to many technology, financial, health care, and government-contracting companies that predominantly hire workers with (at least) a bachelor’s degree. Local student enrollment reflects this demand. Most of NOVA’s 52,000 degree-seeking students (over 70 percent of those who have declared a program of study) are enrolled in transfer-oriented programs. George Mason enrolls over 40,000 students and plans to add 5,000 more by 2030, including transfer students from community colleges.

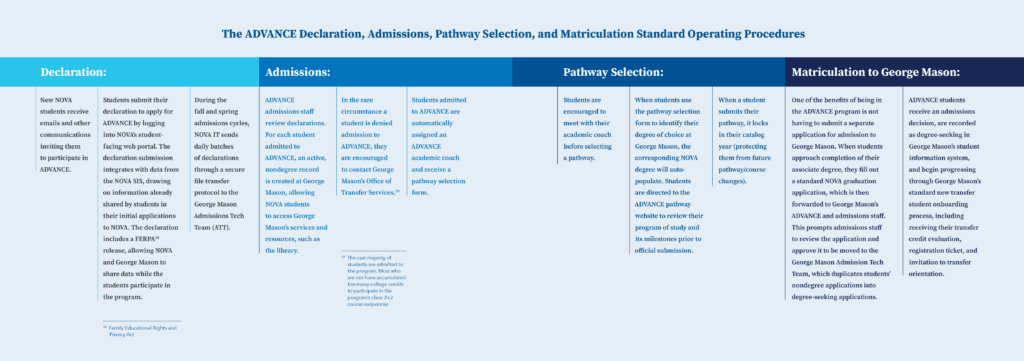

NOVA and George Mason created ADVANCE to improve bachelor’s attainment and increase economic mobility among low- and middle-income individuals and families in their region. ADVANCE is designed to admit thousands of students to both colleges at the same time—often referred to as a dual admissions program—while providing robust student supports and clear academic pathways aligned to high-wage, high-demand jobs. The leaders of NOVA and George Mason structured ADVANCE around four student-centered goals that research shows contribute to students’ success: 1) increase the number of students who attain both an associate and a bachelor’s degree, 2) decrease students’ time to graduation, 3) decrease the cost of a degree (by completing the first 60 credits at NOVA’s lower tuition rate and preventing students from taking excess credits), and 4) improve advising and supports for transfer students. These goals set a clear North Star designed to take an already longstanding, successful partnership to a new level.

The 2017 event that publicly announced ADVANCE communicated the importance of the re-envisioned partnership. The governor of Virginia joined the presidents of George Mason and NOVA, along with major business leaders. At the time, ADVANCE was merely a concept—not a single pathway or structure had been built. Nonetheless, the presidents announced that students could enroll in the program starting the following year. This made it clear that the presidents expected the idea to become a reality, and quickly. Because everyone understood this was a presidential priority, ADVANCE grew from enrolling 129 students in fall 2018 at NOVA to nearly 5,400 in 2024 at NOVA and George Mason.

ADVANCE’s success rates and strong outcomes have made it a national example. Students who transfer to George Mason through ADVANCE take less than two years to complete their bachelor’s degree, on average graduating with seven fewer credits and in one-and-a-half fewer semesters than non-ADVANCE students. Furthermore, these outcomes are promoting economic mobility and opportunity, in particular for underserved groups: Nearly 40 percent of ADVANCE students are eligible for Pell Grants, and 60 percent identify as first-generation college students. And ADVANCE shows no signs of slowing down. At the time of this research, the presidents of NOVA and George Mason continued to meet monthly, discussing opportunities to improve student outcomes and further their institutions’ partnership to meet their shared mission priorities.

In California’s rural Imperial Valley, improving economic opportunity and vitality is a shared goal among leaders of three major educational institutions: Imperial Valley College (IVC), San Diego State University’s local campus, and the county office of K-12 education. Together, they have increased bachelor’s degree attainment in the region and, along the way, enhanced the value the community sees in college-going and degree attainment.

The region, which is heavily agricultural and 85 percent Hispanic, has a poverty rate nearly 60 percent higher than the national average.15 Education and community leaders concluded that improving economic opportunity required increasing the number of residents with bachelor’s degrees so more could secure good-paying jobs in public safety, education, and other service fields and the region could attract more good jobs. They decided to work together to increase the college-going aspirations of high school students while also strengthening transfer pathways between Imperial Valley College (IVC) and San Diego State University-Imperial Valley (SDSU-IV), the only two higher-education institutions in the region.

SDSU-IV was established in 1959 as a satellite campus to broaden college access for Imperial Valley residents who would not or could not travel to pursue their bachelor’s degree. At the time, the closest public universities were over 100 miles away. Programs were designed to meet regional workforce needs—teacher training, nursing, administrative justice, and other fields. Yet, the presence of IVC and SDSU-IV alone was not enough to improve the bachelor’s attainment rate in the region, which stubbornly hovered around 13 percent for decades after SDSU-IV’s creation. Students were confused by uneven academic advising and unclear information about educational paths and credit transfer.

Collaboration has helped change this. The superintendent of the Imperial County Office of Education (ICOE), the president of IVC, and the dean of the SDSU-IV campus now meet at least once a month to discuss opportunities to strengthen the region’s education outcomes and ecosystem, including better transfer pathways, processes, and student success rates. The relationships and conversations have led to innovative and robust high school outreach and advising systems that set a strong foundation for improving transfer from IVC to SDSU-IV (described in Strategies 2 and 3).

Since establishing a common purpose and coordinating stronger and more regular communication and collaboration among educational leaders, the bachelor’s attainment rate for the region has increased to 17 percent.

When presidents prioritize the success of community college transfer students, charge senior-level staff to mobilize their divisions to collaborate, and allocate necessary time, personnel, resources, and visibility to transfer initiatives, they set their partnerships up for success.

The budgetary decisions of college leaders reflected in this research make clear that transfer student success is a priority. Presidents and senior leaders at these exemplars ensure they invest in their institutions and partnerships to support timely implementation and long-term sustainability of their transfer initiatives. These investments often include funding for staff positions, student financial aid, technology, and facilities.

KEY IDEA

Individual and shared investment, including funding and dedicated staff

FIELD EXAMPLES:

Institutions can move the needle on major transfer reforms by investing in transfer-focused staff and giving them the authority to make bold moves. At Virginia Commonwealth University (VCU), the president created the role of associate vice president for transfer initiatives and programs and elevated an experienced administrator to the position. VCU also hired a new senior associate vice president for student success who had a track record of improving transfer.

Those two transfer leaders, with support from the provost and the vice president for enrollment management, established a Transfer Center at VCU that provides advising for prospective transfer students in community college. They also spearheaded the development of transfer maps that outline four years of coursework between VCU and its community college partners (more on page 39). In addition, when VCU decided to invest millions of dollars in professional advising to improve outcomes for new students, transfer leaders made sure the unique needs of transfer students were considered and included in their new processes and systems. (See more about VCU’s advising system in Strategy 3 on page 39).

Together, these major investments and reforms have contributed to VCU’s strong and improving transfer student outcomes. In 2019-20, VCU’s transfer students had a 74 percent four-year graduation rate, up from 69 percent in 2015-16.16

Northern Arizona University’s Yuma campus was established in 1988 to serve the rural southwest Arizona city and surrounding U.S.-Mexico border region. One of its defining features: It is centrally located on Arizona Western College’s largest campus, providing community college students access to an in-person NAU degree without traveling to the main campus in Flagstaff, 300 miles away.

This access to a bachelor’s education is crucial for rural learners seeking to stay in the area. The bachelor’s programs offered are tailored to regional workforce needs to ensure the local community has a home-grown, competitive labor force and graduates can thrive. NAU-Yuma offers programs in high-demand fields such as nursing, education, and logistics and supply chain management, as well as programs aligned to the needs of the border region, such as justice studies and social work.

To deliver these programs and a robust set of student services, NAU-Yuma occupies three buildings on AWC’s campus—requiring a major investment for both institutions. The dedicated space is structured to ensure students have access to key experiences and services that would be available on the main campus. For example, in addition to classroom space, NAU faculty have office space so students can meet with them outside the classroom. The shared spaces also allow for AWC and NAU faculty to align learning outcomes for transfer students. In the Nursing Skills Labs, AWC Nursing Program students prepare for the work they will do in NAU’s Bachelor’s of Nursing program. Additionally, beyond the classroom, the shared spaces provide students with easy, in-person access to NAU administrators and staff who provide a holistic range of student services, from financial aid to academic advising, tutoring, and mental health services. And at the Academic Library, another shared space, librarians support both AWC and NAU-Yuma students, who have access to the same online resources as students at the NAU Flagstaff campus.

The Arizona Board of Regents (the governing board for Arizona’s four-year public universities), approved a specialized line item in NAU’s operating budget for NAU-Yuma as part of its promise to increase postsecondary access and attainment for Arizona students. In 2006, nearly 20 years after its establishment, the regents approved NAU-Yuma as an official branch campus. That allowed NAU-Yuma to seek and receive designation by the U.S. Department of Education as a Hispanic-Serving Institution, opening the door to additional federal funding to further enhance its programs that serve students in Yuma and the surrounding area.

The longstanding and continued investments in the co-located campuses are essential to student success, especially for place-bound students. While AWC graduates can transfer to any NAU campus, including the flagship in Flagstaff, 65 percent choose to enroll at NAU-Yuma.17 However, over the course of their 35-plus-year partnership, AWC and NAU leaders recognized that proximity alone was insufficient to fully meet the needs of their transfer students, who are predominantly first-generation, lower-income, and Hispanic. In recent years, these leaders have collaborated to create a more seamless transition between their institutions, integrating student services like advising and academic supports, strengthening alignment and clarity in their academic pathways, and coordinating their communication with students. See page 47 to read more about the Yuma Educational Success program, which provides one example of how these leaders are making these enhancements.

Northern Virginia Community College (NOVA) and George Mason University both invest significant resources in shared ADVANCE staffing, as well as technology and marketing for the program.18 At the time of this research, ADVANCE had 21 full-time positions, including eight that NOVA and George Mason split the costs for (six academic coaches at NOVA, an associate director of admissions at George Mason, and the executive director of ADVANCE, who reports to leaders at both institutions). These staff support the success of nearly 5,400 students—a number projected to grow.

The investment in adequate staffing levels was made possible because, from the outset, the institutions understood the potential value of the partnership. In the early stages of ADVANCE’s design, the two institutions conducted a financial analysis that projected upfront costs for NOVA in the program’s first two years would be offset by increased retention and completion of associate degrees (historically, most students transferred before they completed their associate degree). The analysis also projected that George Mason would begin to see a return on its upfront investment in year four of the program, assuming they increased the transfer class by 5 percent—a target the university has since exceeded. A long-term forecast showed both partners growing their enrollments—and revenue—and enabled institutional leaders to establish buy-in for substantial investments from key stakeholders, including both institutions’ boards and faculty.

At exemplars studied for this Playbook, leaders established cabinet-supported teams both within and between partner institutions to develop strategies to advance the vision and goals for transfer, implement major transfer initiatives, and ensure the maintenance and continuous improvement of those initiatives. The institutional and partnership teams meet routinely and frequently, and their strong relationships allow them to speak candidly about and address key challenges. These cross-institutional teams also provide other benefits. First, they ensure clear staff ownership and accountability for implementing transfer reforms while promoting collaboration. Second, team structures distribute responsibility for transfer student success, which helps implementation efforts withstand staff turnover. And their regular meetings create a consistent space for academic and student affairs leaders to work together, fostering a holistic approach to addressing the needs of transfer students across institutions.

KEY IDEA

Cabinet-supported teams that advance strategy, implementation, relationship-building, and collaboration

FIELD EXAMPLES:

For several years, Arizona Western College (AWC) and Northern Arizona University (NAU) have convened a team of senior leaders and practitioners to advance significant transfer reforms that meet their presidents’ major goals while also addressing transfer students’ day-to-day needs.

This robust collaboration started soon after a new president took the helm of NAU. His second trip, after meetings in the state capital, was to Yuma and AWC. He and the AWC president spent time together, one-on-one, discussing their shared priorities to connect more local talent to high-wage jobs that require bachelor’s degrees. Because both leaders knew they needed staff to see these priorities through, the NAU president brought along his leadership team to meet with the AWC president’s leadership team.

The teams—clear-eyed about their mandate—split into working groups to address such challenges as recruitment, program offerings, partnership communications, and more. Their discussions helped them develop bold new initiatives, such as a “universal admissions agreement”

in which students who were not immediately accepted to NAU could begin at AWC and expect to transfer without an additional application. They also devised a new partnership structure and communications expectations. For example, the enrollment and advising teams from both institutions continue to meet biweekly, which enables them to quickly resolve challenges and maintain consistent support for students.

Over time, this collaboration has resulted in stronger day-to-day operations and additional investments in the partnership and beyond. For instance, AWC created a dedicated university partnership manager position responsible for supporting students interested in local transfer options, including NAU-Yuma, while NAU added a pre-transfer advisor position. The leadership teams continue their partnership work while also broadening their impact through the NAU-led Arizona Attainment Alliance (A++). The alliance, a collaboration across nine of Arizona’s community college districts and the Arizona Commerce Authority, aims to increase the state’s college attainment rate. AWC was NAU’s founding alliance partner.

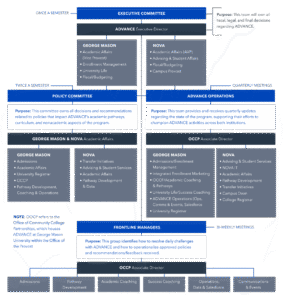

In designing ADVANCE, Northern Virginia Community College (NOVA) and George Mason University created an overarching governance structure that has fostered longevity and success with direct lines to both program and top institutional leaders. In the early years of the program, three committees that included members from both institutions met monthly—student engagement, operations, and policy.19 These committees handled the details of implementing and maintaining ADVANCE and reported to the ADVANCE executive committee, which meets each semester and is managed by the program’s executive director. The executive committee provides a direct line to the provosts and other senior leaders at both institutions, who then report back to NOVA and George Mason’s presidents. At least once a year, the ADVANCE executive director or members of the executive committee support the presidents in reporting to their respective boards.

The cross-institutional governance structure touched on key components of the student experience, such as building and maintaining ADVANCE pathways, advising, and other key operational details, including data-sharing and processing financial aid for students in co-enrollment courses. Also important: The formal governance structure allowed ADVANCE to become institutionalized, so even when staff or college leaders leave, the program remains. Although George Mason and NOVA experienced turnover at the president, provost, and program-level staff during the program’s first five years, ADVANCE continued to meet its goals and expand.

Over the years, ADVANCE’s governance structure has evolved as the program matured and needs changed (reflected in the figure on the next page that depicts ADVANCE’s governance structure for Fiscal Year 2025). For example, now that policies related to ADVANCE are more established, the Policy Committee has reduced its meeting frequency to five times a year, including in the summer. Leaders at NOVA and George Mason expect the ADVANCE governance structure to endure, ensuring that the activities of the program’s 21 dedicated staff are aligned with the latest developments, including leadership turnover, financial forecasts, changes to technology systems, and lessons from regular program evaluation. As both NOVA and George Mason continue to respond to evolving regional needs, this governance structure will ensure the ADVANCE program can keep pace.

Despite other day-to-day responsibilities, staff carved out the time because, as one [person] put it, “I knew it was a priority of my provost and president.”

Essential Practice 2

End-to-end redesign of the transfer student experience

For more community college students to earn a bachelor’s degree, institutions need integrated systems that address the range of transfer student needs: guidance selecting a pathway aligned to student goals, advising and supports to help students make timely progress to degrees, systems that ensure credits transfer to degree programs, and financial aid to make degrees more affordable. Often, colleges working to improve transfer find that effective provision of this range of services and supports requires that they move away from piecemeal structures and supports and reimagine a single model that meets students’ needs from the time they enter college (or before) to the day they graduate with a bachelor’s degree.

Successful institutions and partnerships we studied moved away from a reliance on course articulation agreements as the main tool for helping students transfer and instead adopted comprehensive models that cover the transfer student experience from beginning to end.

These approaches aim to remove confusion and uncertainty by making transfer between two- and four-year institutions seamless and a highly visible or default choice (through guaranteed or dual admissions), promoting an “every student could be a transfer student” mindset. These comprehensive models differ from traditional ones that require students to self-identify as potential transfer students—one of the likely culprits behind disparities in outcomes for historically underserved students. They also sometimes visibly connect transfer pathways to local, high-wage jobs, so students have more reason to persist along the clearer pathways.

KEY IDEAS

- Transformational transfer models that extend beyond

credit articulation - Strategies tailored to regional needs and demographics

- “Every student could be a transfer student” approaches

FIELD EXAMPLES:

At New York City’s John Jay College of Criminal Justice, one out of every two undergraduates is a transfer student, and they attain bachelor’s degrees at high rates. These strong outcomes can be attributed primarily to the CUNY Justice Academy (CJA), which graduates 68 percent of its students within four-years after transfer (compared to 52 percent nationally). CJA is a guaranteed admissions program that provides wraparound support and cohort experiences that enable participants to graduate into in-demand jobs. CJA began with a single major and one community college partner; today, it boasts nine majors and seven partners.

One of the keys to the program’s success is engaging every potential CJA student with a transfer pathway early. As soon as students enroll in a CJA-affiliated major at one of John Jay’s partner community colleges, they receive notice they have been automatically enrolled in CJA, which means guaranteed admission to John Jay after completing an associate degree. While students can opt out of CJA, the automatic-enrollment approach ensures that all students in these majors—regardless of their background—understand that attaining a bachelor’s degree is a realistic option. The notification outlines clear instructions for how to complete the pathway, including four-year major maps that detail courses needed to complete an associate degree, transfer, and graduate with a bachelor’s from John Jay in a timely manner (see more on page 29). CJA program leaders train advisors and professors at partner community colleges so they can answer students’ questions about the program and help them develop tailored education plans based on the four-year major maps.

CJA also ensures the transition to John Jay is as convenient and straightforward as possible. From the students’ perspective, that means minimal administrative burdens and guesswork about next steps. John Jay’s Student Academic Success Programs (SASP) office collaborates with partner community colleges to identify students who are close to completing an associate degree—meaning they have earned at least 55 credits and a 2.0 GPA. Those students are invited to confirm “transition” to John Jay through a short, online form. SASP sends weekly lists of confirmed students to John Jay’s admissions and evaluation offices, where evaluating students’ credits can take six to eight weeks but is usually done more quickly. Next, students receive an email about scheduling an appointment with a John Jay academic advisor. In this 30-minute session—required before classes start—advisors work to resolve any credit transfer issues and help students enroll in their first-semester classes based on the four-year major maps begun at community colleges. After research showed that students were more likely to meet program requirements and degree milestones when they received advising upon entry to John Jay, the college implemented it across the undergraduate population in fall 2023.

CJA got its start with private and federal grant funding. Once the program proved successful for students, the college sought to make it more permanent with funding from its core budget. Others outside the college are also taking note of CJA’s success. The model is beginning to be replicated elsewhere in the CUNY system, such as the BMCC-Baruch Business Academy, a partnership between the Borough of Manhattan Community College and Baruch College.20

At East Carolina University (ECU), a longstanding Bachelor of Science in Industrial Technology (BSIT) transfer program aims to increase bachelor’s attainment for working adults looking to progress in their careers. ECU’s BSIT program offers important insights for the field because national data show that only 48 percent of community college transfer students over age 25 complete a bachelor’s degree four years after transferring (versus 59 percent of all transfer students).21 The BSIT program focuses on students with an associate of applied science degree (AAS), often considered a “terminal” degree that makes it hard to transfer credits to a four-year bachelor’s program. As a result, AAS graduates can enter the workforce quickly but typically face substantial delays as they pursue bachelor’s degrees needed to progress into management positions.

The BSIT program allows students to transfer up to 60 credits from an approved AAS degree, and its concentrations, schedule, and modalities are tailored to the needs of adult students and regional employers. Every year, the university convenes an industry advisory board with regional employers who help ensure that program concentrations align with workforce needs. At the time of this research, the program offered eight concentrations designed to help graduates move into managerial positions (e.g., Distribution and Logistics, Information & Cybersecurity Technology, and Industrial Management). Potential transfer students are encouraged to meet with BSIT advisors, who are trained to ensure that students choose the right program and courses. BSIT’s structure is flexible, designed for the 88 percent of the program’s students who work. For example, six of the eight concentrations can be completed part-time online, and all eight can be completed in person at ECU. For students who prefer in-person classes but can’t make it to ECU’s campus, ECU offers some BSIT concentrations at night at Wake Tech Community College and some BSIT courses at Marine Corps Air Station Cherry Point.

ECU’s data show strong outcomes for students over age 25 who transferred with an AAS. The four-year graduation rate for those students is 58 percent—10 percentage points higher than the national average for older transfer students.22 While these data are not limited to BSIT students, the BSIT program is a major contributor to ECU’s impressive results. Two-thirds of BSIT graduates are over age 25. Despite the majority of students enrolling part-time to accommodate work schedules, the average time for BSIT students to complete a bachelor’s is 2.5 to 3 years from starting the program.

The two counties in Arizona Western College’s service area have very different college-going rates: 57 percent of high school students from Yuma County attend college the year after graduating, while only 34 percent of students from La Paz County do so (the average in Arizona is 48 percent). Yet, neither boasts a strong bachelor’s attainment rate: Yuma’s is 16.4 percent, and

La Paz’s is only 12.4 percent, less than half the rate across the state and the nation (both 33 percent). These data points led AWC leaders to conclude that achieving the “Big Hairy Audacious Goal” of doubling bachelor’s attainment rates in La Paz and Yuma counties by 2035 would require working across the educational pipeline, from high school through bachelor’s completion.23

One of their bets was on dual enrollment. And it was a good bet: Research in the state demonstrates that high school students who take dual enrollment courses are twice as likely to enroll in college than others, and they have stronger first-year retention rates.24 To make dual enrollment more accessible and appealing, the AWC’s District Governing Board in 2017 approved a $25-per-credit-hour tuition rate for students 18 and younger in dual enrollment courses—compared to $97 for other AWC students. Since then, AWC has increased dual enrollment by 617 percent.25

Initially, dual enrollment courses were based on high school partner requests. Now, to increase the likelihood that dual enrollment courses directly connect to degree pathways, AWC and its partners at Yuma Union High Schools are moving toward offering eight specific courses—known as the “elite eight”—at all seven feeder high schools. Each of those eight dual enrollment courses connects to either a workforce credential or a pathway to transfer at a four-year partner.

Transformational Models Combine Reforms that Redesign the Transfer Student Experience

Examples illustrate reforms that can be advanced by partners or individual institutions

Partnership-Driven Examples of Transformational Models and Their Components

NOVA & GMU (ADVANCE)

- Dual admissions

- Academic coaches in community college

- Major-specific four-year pathways

- Limited set of George Mason courses available to NOVA students when community college equivalent is unavailable (co-enrollment)

- Access to George Mason resources (e.g., library, social events) while enrolled at NOVA

- Holistic success coaches at George Mason complement academic advising

- Free tuition for Pell-eligible ADVANCE students

AWC & NAU-Yuma

- Co-location of NAU on AWC’s campus

- Robust, pathway-connected high school dual enrollment

- Wraparound supports that start in high school

- AWC-bound students commit to NAU transfer pathway before high school graduation

- AWC scholarships incentivize academic and nonacademic behaviors associated with transfer success

- Collaborative, four-year advising plan from AWC to NAU

John Jay & Six CUNY Community Colleges (Justice Academy)

- Auto-enrollment in dual admissions for specific majors

- Major-specific four-year pathways

- Systematic advising across transfer experience, including mandatory appointment before matriculating at John Jay

Partnership-Driven Examples of Transformational Models and Their Components

East Carolina (BSIT)

- Specific bachelor’s pathways for AAS completers

- Dedicated, trained advisors

- Most concentrations can be completed in person or online

- On-site delivery at satellite locations with high demand (e.g., local community college, military base)

- Employer-informed, career-connected learning

Tallahassee State College

- Systematic new student onboarding to create tailored education plans by the end of

the first year - Major-specific, four-year pathways (developed with partners) with pre-populated plans/schedules

- Direct registration from tailored plans

Imperial Valley College

- Robust, pathway-connected high school dual enrollment

- Advisors guide admitted high school students in developing a starter degree plan that reflects transfer and/or career goals

- Advising campaign aims for every student to have a tailored degree plan through to graduation/transfer by the end of the student’s first year

Among students we interviewed for this Playbook, college affordability was often the reason they started postsecondary education at a community college. So, it should come as no surprise that many students intending to transfer worried that higher tuition and fees (and possibly room and board) at a four-year institution would make earning a bachelor’s degree unaffordable. Small scholarships from community colleges and transfer destinations helped ease some students’ concerns. The university partners in our research were particularly attentive to providing transfer students with robust financial aid and making sure students knew about it.

KEY IDEA

Increase attention to affordability and financial aid

FIELD EXAMPLES:

For students at community colleges in the University of Arkansas System, financial worries about higher costs after they transfer are eased by a scholarship program from the University of Arkansas Fayetteville (UAF) that holds tuition at community college levels if students transfer to the state flagship. Students are eligible for automatic admission to UAF and the scholarship if they (1) complete an associate degree, (2) have GPAs above 2.0, (3) transfer immediately after associate completion, and (4) enroll as degree-seeking undergraduates in a face-to-face program (which can include online courses). By maintaining good academic standing and continuous enrollment, transfer students can renew their scholarship for up to 10 terms or completion of a bachelor’s degree, whichever comes first.

About 40 percent of ADVANCE students enrolled at Northern Virginia Community College (NOVA) are Pell Grant-eligible. For these students, a financial aid program called the Mason Virginia Promise Grant (MVP) covers all their remaining tuition and fees after other aid has been applied. This grant helps eliminate uncertainty for lower-income ADVANCE students about whether they will be able to afford to transfer to George Mason University and complete a bachelor’s degree—allowing them to focus more on their studies and less on how to pay for tuition.

With the success of ADVANCE, George Mason has expanded the program to five additional community colleges in Virginia, and low-income students from those colleges are eligible for the MVP grant.

Essential Practice 3

Routinized, transfer student-centered systems and process

In our research, we observed that many high-performing transfer partners routinize important improvements in the transfer process, such as credit transfer, data sharing, and applications. These routines seemed to (1) increase the chances those practices were maintained at a scale needed to substantially improve student success (even in the face of staff and leadership turnover) and (2) create more consistency by reducing reliance on individual students, staff, or faculty members’ knowledge to complete key steps in the transfer process.

Transfer can be administratively burdensome for students. In addition to filling out new admissions applications, they can face multiple requests for transcripts for credit evaluation. And at their new institutions, they encounter new systems for choosing a major, registering for courses, and accessing financial aid. Some of the exemplars we studied used information technology to reduce the administrative burden on students and, in some cases, faculty members and advisors. Automated and predictable transfer processes were easier for students to navigate.

KEY IDEA

Automation, technology, and predictable processes to improve student experiences at scale

FIELD EXAMPLES:

A well-documented impediment to transfer student success: Too many credits do not transfer or transfer but don’t apply to degree programs when students move from community college to a four-year institution.26 Aware of the delays and financial burdens this causes transfer students, the University of North Texas (UNT) aims to maximize credit mobility as part of its broader priority of promoting affordability.

To uphold academic rigor, UNT invests in staff and has established clear processes for determining whether prior coursework adequately prepares students for success. UNT has three full-time staff who, among other responsibilities, coordinate the development of four-year degree maps for every major. Each college and department are responsible for updating the maps in collaboration with their community college counterparts, a process made easier by the Texas Common Course Numbering System, which is mandatory for community colleges and voluntary for universities.

UNT also convenes at least three faculty experts, a program administrator, and a curriculum review committee when credits from a course or applied/technical program, or credits for prior learning are being reviewed for the first time. Together, the group works to reduce the chance of bias or human error while balancing two goals: maximizing credits that will transfer and ensuring the quality of credits UNT accepts.

With nearly 37 percent of its graduates completing 30 or more credits in community college, UNT recognizes that it must make sure its efforts to maximize credit applicability support students at scale.27 Once any credit is articulated, the rules associated with that credit are integrated into the university’s degree audit system (e.g., the credit applies to degree requirements for specific programs, it transfers as an elective, etc.). That way, students or advisors with the same question about credit applicability have quick access to the answer.

When George Mason University and Northern Virginia Community College (NOVA) leaders designed ADVANCE, they projected that several thousand students would enroll. They knew they had to create standardized, repeatable processes, so they invested heavily in developing data sharing and workflows across both institutions, each of which utilized different student information systems (SIS), customer relationship management (CRM) platforms, and other technology systems. As a result, NOVA students can easily join the ADVANCE program, identify a program of study, gain admission to George Mason, and get access to ADVANCE academic coaches while at NOVA.

The comprehensive ADVANCE process described below required substantial upfront investment of money and staff time. Despite other day-to-day responsibilities, staff carved out the time because, as one IT professional put it, “I knew it was a priority of my provost and president.” While not every transfer partnership has the scale or resources to implement all of these systems, it is worth considering which of the automated processes the ADVANCE partners implemented can be replicated at other institutions.

Colleges studied for this Playbook prioritized collecting and sharing data on transfer students disaggregated by key demographic factors such as income, working status, and race/ethnicity. This helped administrators, faculty, and staff make informed decisions about how to improve pathways and support for transfer students.

KEY IDEA

Actionable, disaggregated data to promote accountability, support case-making, and inform continuous improvement

FIELD EXAMPLES:

At Durham Tech’s Transfer Center, prospective transfer students have access to dedicated advisors, workshops, and other resources to navigate their university applications, financial aid, and degree planning. Durham Tech works to consistently improve those services for all student groups.

One example: The leader of the college’s Transfer Center disaggregates the center’s utilization rates by student demographics and includes that analysis in an annual report the college uses to make improvements. For instance, a recent report noted that Hispanic students were making good use of the Transfer Center, but Black students were not. In response, Transfer Center staff reached out to Black student affinity groups to promote the center’s services and alerted advisors so they could increase referrals to the center. These and other efforts had an impact at Durham Tech, where the percentage of Black students visiting the Transfer Center went up 5 percentage points in two years, from 26 to 31 percent.

The University of North Texas (UNT) consistently collects and reports disaggregated data on transfer student outcomes through its Insights Program. The university-wide initiative, launched in 2015 by UNT’s then-president, tracks metrics on enrollment, financial aid, grading patterns, retention, graduation, and student engagement. The program can disaggregate all metrics by transfer status, allowing UNT to make strategic decisions to improve transfer students’ outcomes when gaps are identified.

Use of the Insights Program dashboards—accessible to all faculty and staff—has resulted in concrete improvements for transfer students. For example, UNT leaders used the dashboards to determine that (1) financial need was contributing to community college transfer student attrition and (2) transfer students were more likely to work longer hours and take fewer credits than other students. So, UNT leaders invested in additional financial aid for transfer students, including extending scholarship eligibility from two semesters to four.

Insights Program leaders conduct regular training across departments, resulting in increased data literacy and more widespread data use in transfer and other strategic focus areas.

Data-driven strategies like these enabled UNT to increase its four-year community college transfer student graduation rate from 57 percent in 2014 to 65 percent in 2023.30

While quantitative data can help colleges understand transfer student successes and challenges, qualitative data are usually needed to shed light on student experiences and what institutional practices may be contributing to or hindering students’ success. However, even exemplary institutions were less likely to use qualitative data to understand student perspectives than they were to use quantitative data on transfer outcomes. For the few that gathered information systematically, qualitative student experience data informed strategic investments or cuts to less effective programming.

Northern Virginia Community College (NOVA) and George Mason University regularly survey ADVANCE students and use that information to improve support services and transfer pathways. Among other things, survey results help program leaders track the use of services. One year’s survey showed that while over 90 percent of ADVANCE students responding to the survey engaged with their academic coach and accessed curricular pathways, far fewer knew about other services, such as George Mason’s free shuttle bus. So, ADVANCE added a coordinator of events and communications to increase student awareness and use of valuable tools and services.

Strategy 2: Align Program Pathways and High-Quality Instruction to Promote Timely Bachelor’s Completion within a Major

Summary: This strategy is characterized by three essential practices, each featuring several key ideas:

For transfer students to succeed, they need clear, high-quality academic pathways from community college entry through bachelor’s completion. College exemplars studied for this Playbook achieve this in three ways: First, they work to ensure that each pathway includes strong academic preparation and is designed for timely transfer and bachelor’s completion. Second, they create schedules that suit students’ individual needs and life circumstances. Finally, they consistently encourage faculty to foster a culture that supports transfer student success both in and outside coursework.

Essential Practice 1

Four-year sequences that promote learning and major progression

The strongest partnerships develop and maintain clear, program-specific, and structured transfer pathways to support timely degree progress within a major. Ultimately, these pathways address what students care about most—achieving their career goals and affording the cost of college. Clear pathways also ensure that any community college student can see whether they are on track to a bachelor’s degree. For college leaders, faculty, and staff the ultimate standard for transfer pathways includes academically rigorous course sequences that can be realistically completed in four years.

The concept of a four-year map is simple: the sequence of courses (or options) a community college student needs to take to transfer and complete a bachelor’s degree at a specific university in a specific major within four years of full-time study or an equivalent number of credits (most often 120).

Hundreds of community colleges have developed program maps as part of guided pathways reforms—an effort to clarify, simplify, and strengthen programmatic pathways, academic advising, and other supports to improve student outcomes.31 A smaller number of four-year institutions have followed suit. Most often, community college maps cover one or two years of coursework, reflecting what students should take to complete a certificate or associate degree. In contrast, the colleges in our research created well-thought-out, four-year maps that are pressure tested and maintained by faculty and can be readily customized for individual students.

In addition to helping community college students, the four-year maps provide a clear benchmark for success during faculty-to-faculty collaboration to develop or refine transfer pathways (discussed in Essential Practice 3 in this section). Maps that cover all four years to a bachelor’s degree make it easier for faculty and staff to identify when students are taking excess credits or misaligned courses.

While the standard four-year map assumes two years at a community college and two years at a four-year institution, some look different. Alternatives such as 1+3 (one year at a community college and three years at a four-year institution) and 3+1 programs can be considered when issues such as the availability of equipment, faculty, and courses at one institution in a partnership pose barriers to the typical 2+2 model.

Ultimately, four-year maps provide students clarity, consistency, and reassurance that courses will transfer and apply toward a degree without excess credits. If they are carefully constructed, embedded into technology systems, regularly updated, and used by both students and advisors, four-year maps should save students time and money.

KEY IDEA

Create and maintain clear, term-by-term, four-year maps within each major that set expectations for timely completion and are adjustable for part-time students

“They literally give you a sheet of paper with the classes you need to take so you can transfer and get that bachelor’s degree. It just makes it so simple and stress free.”

— Transfer Student

FIELD EXAMPLES:

Our research discovered several examples of strong four-year maps, including at the University of North Texas (UNT), Virginia Commonwealth University (VCU), and the ADVANCE program at Northern Virginia Community College (NOVA) and George Mason University. Each map had its own unique features. For example, ADVANCE provides a list of NOVA and George Mason courses that students can arrange to fit their schedules, while UNT presents specific courses, term by term. At VCU, major maps include not just course recommendations but also steps students should take to explore careers. While the development of many of the four-year maps featured in this research was led by four-year institutions—independently or in partnership with community colleges—we also found examples of community colleges leading the mapping process. However, without collaboration with four-year faculty, those maps often incorporated fewer major-specific courses, which could lead to challenges once students transfer.

The example highlighted below is based on the four-year degree plans from CUNY Justice Academy and

John Jay College of Criminal Justice, which incorporate the key components of strong maps identified in the following section.

The quality of four-year maps ultimately depends on the strength of the academic programs they portray. So, to develop quality four-year maps, many colleges need to strengthen transfer programs. At the community college level, many transfer-oriented associate degree programs overemphasize general education requirements. While this can help students accumulate credits that can be applied to different majors, it often creates barriers for students by delaying their choice of major and failing to engage them in major-specific content. Conversely, at the university level, many transfer pathways reflect an expectation that associate degree graduates will complete upper-division degree requirements at a faster pace than those who would have started as first-year students or, for the reasons described below, take longer to graduate.

The exemplars in our research went beyond designing degrees and pathways that transferred or satisfied general education requirements. They created programmatic pathways, starting in community college, that ensure credit applicability and timely progression within a major.

KEY IDEAS

- Frontload courses that inspire early major exploration, commitment, or changes

- Expect at least one major-specific course each term in community college

- Embed college-level, program-specific math and English in the first year

Because four-year maps set an explicit benchmark for pathway design, they make it easier for faculty and staff to identify when there are excess credits and course misalignments. Their development and existence provide a clear starting point for faculty-to-faculty collaboration.

These course sequences have three features:

First, the exemplars include major-specific courses (e.g., a biology course for prospective biology majors) in the first term. This enables students to either commit to their program with greater confidence and enthusiasm or change direction while there is still time to make early progress on a different pathway. Switching majors early avoids adding time to a degree or excess credits, as one or two major-specific courses can usually be converted into electives or satisfy general education requirements for a different major. Prior research demonstrated that STEM transfer students who take a STEM course in their first term are more likely to persist on a STEM transfer path.32

Second, exemplars ensured that most students in a 2+2 pathway were taking classes that prepared them to transfer with junior-level status within a major at a pace comparable to students who began at the four-year institution. This means community college students take the same major-specific courses (or preapproved equivalents) as students who start at the four-year institution (i.e., approximately one major-specific course each term for a full-time student). This approach is distinct from defining junior status simply by the number of credits earned. Students benefit from this approach in two ways: They gain broader exposure to their chosen discipline before transferring, and they are better prepared to complete their upper-division major requirements and electives in a timely manner after transferring.

Delaying major-specific courses poses several risks. Students can become overburdened with too many high-degree-of-difficulty major requirements after transferring, which could lead to burnout and lower completion rates. Alternatively, both scheduling constraints (i.e., a course is available only once each academic year) and the need to space out highly challenging major requirements can result in transfer students paying more tuition and increasing the time needed to complete their degrees. Students can also experience delayed or denied admission to their major if they can’t take enough prerequisites, especially to competitive (and often remunerative) majors. Each of these consequences would disproportionately harm lower-income students, who may not be able to afford to delay graduation and may run out of financial aid eligibility.

For programs in which students can’t maximize major-specific courses at the community college, transfer partners should consider transitioning pathways to 1+3 or other alternative formats to ensure students can transfer and progress to a bachelor’s with few, if any, excess credits. Another option is to establish co-enrollment—where prospective transfer students continue to take most courses at community college while taking one or more individual major-specific courses at the university that are otherwise unavailable.

Finally, exemplary transfer maps often include specific college-level math and English courses in the first year, differentiated by a student’s program of study (e.g., calculus for engineering majors, statistics for psychology majors). This is consistent with studies that demonstrate students—especially historically underserved students—are much more likely to be transfer-ready, transfer, and earn bachelor’s degrees after completing these specific courses in their first year.33,34 Unfortunately, many students do not take these courses early. One common barrier is long, non-credit developmental education sequences. Essential Practice 3 in this section addresses how community college exemplars studied for this Playbook moved away from prerequisite developmental education sequences to support early college-level math and English completion.

Taken together, these features—all designed to support timely bachelor’s degree completion within a major—substantially improve pathways for community college students seeking a bachelor’s degree. Later in this section, we describe how community colleges and universities collaborated to develop these high-caliber programmatic pathways.

An Opportunity for State or System Policy

We compared the strong maps and pathways at the Playbook exemplar institutions with those from other institutions, systems, and states. We found that, unlike at the colleges featured in this section, the issue of students taking insufficient major-specific courses in community colleges is widespread. Even institutions in states and systems with mandated transfer pathways have maps that recommend transfer students take only two major-specific courses for many majors, especially in STEM disciplines (i.e., an introductory course and perhaps the second in a first-year sequence). This reveals a flaw—and opportunity—in state and system-level policies on transfer pathways. Our finding is consistent with other research on statewide transfer pathways, which have been shown to strengthen transfer rates but have limited impact on bachelor’s completion, credit accumulation, and time to degree.35,36

Essential Practice 2

Systematized translation of maps into tailored education plans

Four-year maps can be important tools for transfer students and advisors. However, the full benefit of maps is realized only when a student works with an advisor to translate a map into an editable, digitized education plan tailored to their circumstances. Such plans can be powerful tools, especially for the two-thirds of community college students who do not enroll full-time. Creating tailored educational plans with advisors helps those students understand how to maximize progress toward their associate and bachelor’s degrees in ways that take into consideration their time constraints.

The exemplars in our research were especially attentive to developing systems that enable program maps to be translated into tailored plans for students at scale. Their systems included three standout features: